Motivation

Chapter 5

History as Trajectory

Prologue

Our history is the prologue to the network state.

This is not obvious. Founding a startup society as we’ve described it seems to be about growing a community, writing code, crowdfunding land, and eventually attaining the diplomatic recognition to become a network state. What does history have to do with anything?

The short version is that if a tech company is about technological innovation first, and company culture second, a startup society is the reverse. It’s about community culture first, and technological innovation second. And while innovating on technology means forecasting the future, innovating on culture means probing the past.

But why? Well, for a tech company like SpaceX you start with time-invariant laws of physics extracted from data, laws that tell you how atoms collide and interact with each other. The study of these laws allows you to do something that has never been done before, seemingly proving that history doesn’t matter. But the subtlety is that these laws of physics encode in highly compressed form the results of innumerable scientific experiments. You are learning from human experience rather than trying to re-derive physical law from scratch. To touch Mars, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

For a startup society, we don’t yet have eternal mathematical laws for society.72 History is the closest thing we have to a physics of humanity. It furnishes many accounts of how human actors collide and interact with each other. The right course of historical study encodes, in compressed form, the results of innumerable social experiments. You can learn from human experience rather than re-deriving societal law from scratch. Learn some history, so as not to repeat it.

That’s a theoretical argument. An observational argument is that we know that the technological innovation of the Renaissance began by rediscovering history. And we know that the Founding Fathers cared deeply about history. In both cases, they stepped forward by drawing from the past. So if you’re a technologist looking to blaze a trail with a new startup society, that establishes plausibility for why historical study is important.

The logistical argument is perhaps the most compelling. Think about how much easier it is to use an iPhone than it was to build Apple from scratch. To consume you can just click a button, but to produce it’s necessary to know something about how companies are built. Similarly, it’s one thing to operate as a mere citizen of a pre-built country, and quite another thing to create one from scratch. To build a new society, it’d be helpful to have some knowledge of how countries were built in the first place, the logistics of the process. And this again brings us into the domain of history.

Why History is Crucial

You can’t really learn something without using it. One day of immersion with a new language beats weeks of book learning. One day of trying to build something with a programming language beats weeks of theory, too.

In the same way, the history we teach is an applied history: a crucial tool for both the prospective president of a startup society73 and for their citizens, shareholders, and staff. It’s something you’ll use on a daily basis. Why?

-

History is how you win the argument. Think about the 1619 Project, or the grievance studies departments at universities, or even a newspaper “profile” of some unfortunate. You might be mining cryptocurrency, but the folks behind such things are mining history. That is, many thousands of people are engaged full time in “offense archaeology,” the excavation of the recent and distant past for some useful incident they can write up to further demoralize their political opposition. This is the scholarly version of going through someone’s old tweets. It’s weaponized history, history as opposition research. You simply can’t win an argument against such people on pure logic alone; you need facts, so you need history.

-

History determines legality. We denote the exponential improvement in transistor density over the postwar period by Moore’s law. We describe the exponential decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency during the same period as Eroom’s law — as Moore’s law in reverse. That is, over the last several decades, the FDA somehow presided over an enormous hike in the costs of drug development even as our computers and our knowledge of the human genome vastly improved. Similar phenomena can be observed in energy (where energy production has stagnated), in aviation (where top speeds have topped out), and in construction (where we build slower today than we did seventy years ago).

Obviously, even articulating Eroom’s law requires detailed knowledge of history, knowledge of how things used to be. Less obviously, if we want to change Eroom’s law, if we want to innovate in the physical world again, we’ll need history too.

The reason is that behind every FDA is a thalidomide, just as behind every TSA there’s a 9/11 and behind every Sarbanes-Oxley is an Enron. Regulation is dull, but the incidents that lead to regulation are anything but dull.

This history is used to defend ancient regulations; if you change them, people will die! As such, to legalize physical innovation you’ll need to become a counter-historian. Only when you understand the legitimating history of regulatory agencies better than their proponents do can you build a superior alternative: a new regulatory paradigm capable of addressing both the abuses of the American regulatory state and the abuses they claim to prevent.

-

History determines morality. Religions start with history lessons. You might think of these as made-up histories, but they’re histories all the same. Tales of the distant past, fictionalized or not, that describe how humans once behaved - and how they should have behaved. There’s a moral to these stories.

Political doctrines are based on history lessons too. They’re how the establishment justifies itself. The mechanism for propagating these history lessons is the establishment newspaper, wherein most articles aren’t really about true-or-false, but good-and-bad. Try it yourself. Just by glancing at a headline from any establishment outlet, you can instantly apprehend its moral lesson: x-ism is bad, our system of government is good, tech founders are bad, and so on. And if you poke one level deeper, if you ask why any of these things is good or bad, you’ll again get a history lesson. Because why is x-ism bad? Well, let me educate you on some history…

The installation of these moral premises is a zero-sum game. There’s only room for so many moral lessons in one society, because a brain’s capacity for moral computation is limited. So you get a totally different society if 99% of people allocate their limited moral memory to principles like “hard work good, meritocracy good, envy bad, charity good” than if 99% of people have internalized nostrums like “socialism good, civility bad, law enforcement bad, looting good.”74 You can try to imagine a scenario where these two sets of moral values aren’t in direct conflict, but empirically those with the first set of moral values will favor an entrepreneurial society and those with the second set of values will not.75

-

History is how you develop compelling media. You can make up entirely fictional stories, of course. But even fiction frequently has some kind of historical antecedent. The Lord of the Rings drew on Medieval Europe, Spaghetti Westerns pulled from the Wild West, Bond movies were inspired by the Cold War, and so on. And certainly the legitimating stories for any political order will draw on history.

-

History is the true value of cryptocurrency. Bitcoin is worth hundreds of billions of dollars because it’s a cryptographically verifiable history of who holds what BTC. Read The Truth Machine for a book-length treatment of this concept.

-

History tells you who’s in charge. Why did Orwell say that he who controls the past controls the future, and that he who controls the present controls the past? Because history textbooks are written by the winners. They are authored, subtly or not, to tell a story of great triumph by the ruling establishment over its past enemies. The only history most people in the US know is 1776, 1865, 1945, and 1965 - a potted history of revolutions, world wars, and activist movements that lead ineluctably to the sunny uplands of greater political equality.76 It’s very similar to the history the Soviets taught their children, where all of the past was interpreted through the lens of class struggle, bringing Soviet citizens to the present day where they were inevitably progressing from the intermediate stage of socialism towards…communism! Chinese schoolchildren learn a similarly selective history where the (real) wrongs of the European colonialists and Japanese are centered, and those of Mao downplayed. And even any successful startup tells a founding story that sands off the rough edges.

In short, a history textbook gives you a hero’s journey that celebrates the triumph of its establishment authors against all odds. Even when a historical treatment covers ostensible victims, like Soviet textbooks covering the victimization of the proletariat, if you look carefully the ruling class that authors that treatment typically justifies itself as the champion of those victims. This is why one of the first acts of any conquering regime is to rewrite the textbooks (click those links), to tell you who’s in charge.

-

History determines your hiring policy. Why are tech companies being lectured by media corporations on “diversity”? Is it because those media corporations that are 20-30 points whiter than tech companies actually deeply care about this? Or is it because after the 2009-era collapse of print media revenue, media corporations struggled for a business model, found that certain words drove traffic, and then doubled down on that - boosting their stock price and bashing their competitors in the process?77 After all, if you know a bit more history, you’ll know that the New York Times Company (which originates so many of these jeremiads) is an organization where the controlling Ochs-Sulzberger family literally profited from slavery, blocked women from being publishers, excluded gays from the newsroom for decades, ran a succession process featuring only three cis straight white male cousins, and ended up with a publisher who just happened to be the son of the previous guy.78

Suppose you’re a founder. Once you know this history, and once all your friends and employees and investors know it, and once you know that no purportedly brave establishment media corporation would have ever informed you of it in quite those words79, you’re outside the matrix. You’ve mentally freed your organization. So long as you aren’t running a corporation based on hereditary nepotism where the current guy running the show inherits the company from his father’s father’s father’s father, you’re more diverse and democratic than the owners of The New York Times Company. You don’t need to take lectures from them, from anyone in their employ, or really from anyone in their social circle — which includes all establishment journalists. You now have the moral authority to hire who you need to hire, within the confines of the law, as SpaceX, Shopify, Kraken, and others are now doing. And that’s how a little knowledge of history restores control over your hiring policy.

-

History is how you debug our broken society. Many billions of dollars are spent on history in the engineering world. We don’t think about it that way, though. We call it doing a post-mortem, looking over the log files, maybe running a so-called time-travel debugger to get a reproducible bug. Once we find it, we might want to execute an undo, do a

git revert, restore from backup, or return to a previously known-good configuration.Think about what we’re saying: on a micro-scale, knowing the detailed past of the system allows us to figure out what had gone wrong. And being able to partially rewind the past to progress along a different branch (via a

git revert) empowers us to fix that wrongness. This doesn’t mean throwing away everything and returning to the caveman era of a blank git repository, as per either the caricatured traditionalist who wants to “turn back the clock” or the anarcho-primitivist who wants to end industrialized civilization. But it does mean rewinding a bit to then move forward along a different path80, because progress has both magnitude and direction. All these concepts apply to debugging situations at larger scale than companies — like societies, or countries.81

You now see why history is useful. A founder of a mere startup company can arguably scrape by without it, tacitly outsourcing the study of history to those who shape society’s laws and morality. But a president of a startup society cannot, because a new society involves moral, social, and legal innovation relative to the old one — and that requires a knowledge of history.

Why History is Crucial for Startup Societies

We’ve whetted the appetite with some specific examples of why history is useful in general. Now we’ll describe why it’s specifically useful for startup societies.

We begin by introducing an operationally useful set of tools for thinking about the past from a bottom-up and top-down perspective: history as written to the ledger, as opposed to history as written by the winners.

We use these tools to discuss the emergence of a new Leviathan, the Network, a contender for the most powerful force in the world, a true peer (and complement) to both God and the State as a mechanism for social organization.

And then we’ll bring it all together in the lead-up to the key concept of this chapter: the idea of the One Commandment, a historically-founded sociopolitical innovation that draws citizens to a startup society just as a technologically-based commercial innovation attracts customers to a startup company.

If a startup begins by identifying an economic problem in today’s market and presenting a technologically-informed solution to that problem in the form of a new company, a startup society begins by identifying a moral issue in today’s culture and presenting a historically-informed solution to that issue in the form of a new society.

Why Startup Societies Aren’t Solely About Technology

Wait, why does a startup society have to begin with a moral issue? And why does the solution to that moral issue need to be historically-informed? Can’t it just be a tech-focused community where people solve problems with equations? We’re interested in Mars and life extension, not dusty stories of defunct cities!

The quick answer comes from Paul Johnson at the 11:00 mark of this talk, where he notes that early America’s religious colonies succeeded at a higher rate than its for-profit colonies, because the former had a purpose. The slightly longer answer is that in a startup society, you’re not asking people to buy a product (which is an economic, individualistic pitch) but to join a community (which is a cultural, collective pitch). You’re arguing that the culture of your startup society is better than the surrounding culture; implicitly, that means there’s some moral deficit in the world that you’re fixing. History comes into play because you’ll need to (a) write a study of that moral deficit and (b) draw from the past to find alternative social arrangements where that moral deficit did not occur. Tech may be part of the solution, and calculations may well be involved, but the moment you write about any societal problem in depth you’ll find yourself writing a history of that problem.

For specifics, you can skip ahead to Examples of Parallel Societies — or you can suspend disbelief for a little bit, keep reading, and trust us that this historical/moral/ethical angle just might be the missing ingredient to build startup societies, which after all haven’t yet fully taken off in the modern world.

Applied History for Startup Societies

Here’s the outline of this chapter.

-

We start with bottom-up history. The section on Microhistory and Macrohistory bridges the gap between the trajectory of an isolated, reproducible system and the trajectories of millions of interacting human beings. Because both these small and large-scale trajectories can now be digitally recorded and quantified, this is history as written to the ledger — culminating in the cryptohistory of Bitcoin.

-

We next discuss top-down history. This is history as written by the winners, history as conceptualized by what Tyler Cowen calls the Base-Raters, history that justifies the current order and proclaims it stable and inevitable. It is a theory of Political Power vs. Technological Truth.

-

We then talk about the history of power, giving names to the forces we just described by identifying the three candidates for most powerful force in the world: God, State, and Network. Framing things in terms of three prime movers rather than one allows us to generalize beyond purely God-centered religions to understand the Leviathan-centered doctrines that implicitly underpin modern society.

-

We apply this to the history of power struggles. With the God/State/Network lens, we can understand the Blue/Red and Tech-vs-Media conflicts in a different way as a multi-sided struggle between People of God, People of the State, and People of the Network.

-

We go through how the People of the State have used their power to distort recent and distant history, and how the Network is newly rectifying this distortion in “If the News is Fake, Imagine History.”

-

Having shown the degree to which history has been distorted, and thereby displaced the (implicit) historical narrative in which the arc of history bends to the ineluctable victory of the US establishment82, we discuss several alternative theories of past and future in our section on Fragmentation, Frontier, Fourth Turning, and Future Is Our Past. These theses don’t describe a clean progressive victory on every axis, but instead a set of cycles, hairpin turns, and mirror images, a set of historical trajectories far more complex than the narrative of linear inevitability smuggled in through textbooks and mass media.

-

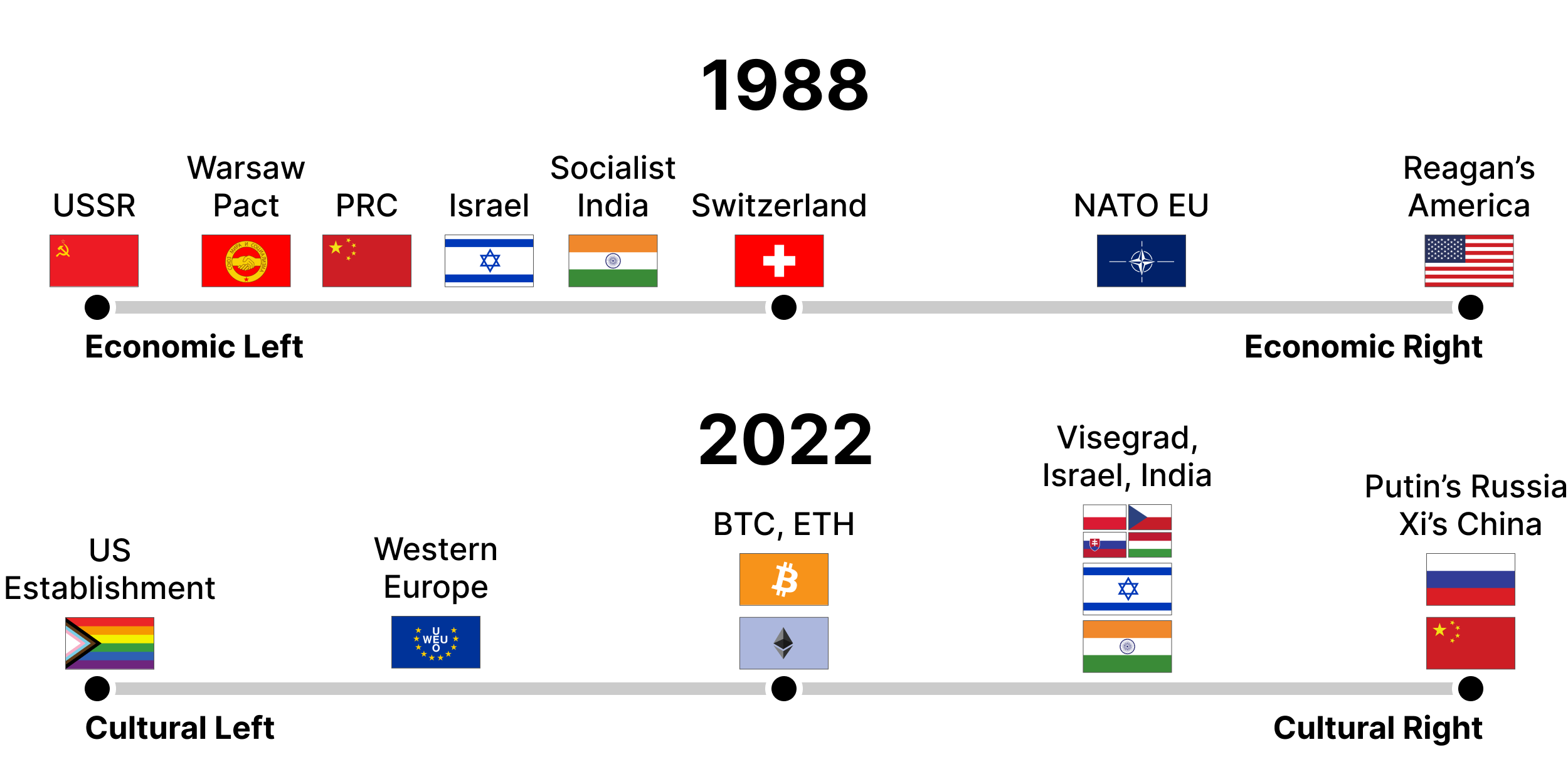

We next turn our attention to left and right, which are confusing concepts in a realigning time, in Left is the new Right is the new Left. Sorry! We can’t avoid politics anymore. Startup societies aren’t purely about technology. But please note that for the most part this section isn’t the same old pabulum around current events. We do contend that you need a theory of left and right to build a startup society, but that doesn’t mean just picking a side.

Why? While a political consumer has to pick one of a few party platforms off the menu, a political founder can do something different: ideology construction. To inform this, we’ll show how left and right have swapped sides through history, and how any successful mass movement has both a revolutionary left component and a ruling right component.

-

Finally, all of this builds up to the payoff: the One Commandment. Using the terminology we just introduced, we can rattle it off in a few paragraphs. (If the following is opaque in any way, read the chapter, then come back and re-read this part.)

If history is not pre-determined to bend in one direction, if the current establishment may experience dramatic disruption in the form of the Fragmentation and Fourth Turning, if its power actually arose from the expanding frontier rather than the expanding franchise, if history is somehow running in reverse as per the Future Is Our Past thesis, if the revolutionary and ruling classes are in fact switching sides, if the new Leviathan that is the Network is indeed rising above the State, and if the internal American conflicts can be seen not as policy disputes but as holy wars, as clashes of Leviathans…then the assumption of the Base-Raters that all will proceed as it always has is quite incorrect! But rather than admit this incorrectness, they’ll attempt to use political power to suppress technological truth.

The founder’s counter is cryptohistory and the startup society. We now have a history no establishment can easily corrupt, the cryptographically verifiable history pioneered by Bitcoin and extended via crypto oracles. We also have a theory of historical feasibility, history as a trajectory rather than an inevitability, the idea that the desirable future will only occur if you put in individual effort. But what exactly is the nature of that desirable future?

After all, many groups differ with the old order but also with each other — so a blanket solution won’t work. And could well be resisted. That’s where the One Commandment comes in.

As context, the modern person is often morally reticent but politically evangelistic. They hesitate to talk about what is moral or immoral, because it’s not their place to say what’s right. Yet when it comes to politics, this diffidence is frequently replaced by overbearing confidence in how others must live, coupled with an enthusiasm for enforcing their beliefs at gunpoint if necessary.

In between this zero and ∞, in between eschewing moral discussion entirely and imposing a full-blown political doctrine, in this final section we propose a one: a one commandment. Start a new society with its own moral code, based on your study of history, and recruit people that agree with you to populate it.83 We’re not saying you need to come up with your own new Ten Commandments, mind you — but you do need One Commandment to establish the differentiation of a new startup society.

Concrete examples of possible One Commandments include “24/7 internet bad” (which leads to a Digital Sabbath society), or “carbs bad” (which leads to a Keto Kosher society), or “traditional Christianity good” (which leads to a Benedict Option society), or “life extension good” (which leads to a post-FDA society).

You might think these One Commandments sound either trivial or unrealistically ambitious, but in that respect they’re similar to tech; the pitch of “140 characters” sounded trivial and the pitch of “reusable rockets” seemed unrealistic, but those resulted in Twitter and SpaceX respectively. The One Commandment is also similar to tech in another respect: it focuses a startup society on a single moral innovation, just like a tech company is about a focused technoeconomic innovation.

That is, as we’ll see, each One Commandment-based startup society is premised on deconstructing the establishment’s history in one specific area, erecting a replacement narrative in its place with a new One Commandment, then proving the socioeconomic value of that One Commandment by using it to attract subscriber-citizens. For example, if you can attract 100k subscribers to your Keto Kosher society through deeply researched historical studies on the obesity epidemic, and then show that they’ve lost significant weight as a consequence, you’ve proven the establishment deeply wrong in a key area. That’ll either drive them to reform — or not reform, in which case you attract more citizens.

A key point is that we can apply all the techniques of startup companies to startup societies. Financing, attracting subscribers, calculating churn, doing customer support — there’s a playbook for all of that. It’s just Society-as-a-Service, the new SaaS.

In parallel, other startup societies are likewise critiquing by building, draining citizens away from the establishment with their own historically-informed One Commandments, and thereby driving change on other dimensions. Finally, different successful changes can be copied and merged together, such that the second generation of startup societies starts differentiating from the establishment by two, three, or N commandments. This is a vision for peaceful, parallelized, historically-driven reform of a broken society.

Ok! I know those last few paragraphs involved some heavy sledding, but come back and reread them after going through the chapter. The main point of our little preview here was to make the case that history is an applied subject — and that you can’t start a new society without it.

Without a genuine moral critique of the establishment, without an ideological root network supported by history, your new society is at best a fancy Starbucks lounge, a gated community that differs only in its amenities, a snack to be eaten by the establishment at its leisure, a soulless nullity with no direction save consumerism.84

But with such a critique — with the understanding that the establishment is morally wanting, with a focused articulation of how exactly it falls short, with a One Commandment that others can choose to follow, and with a vision of the historical past that underpins your new startup society much as a vision of the technological future underpins a new startup company — you’re well on your way.

You might even start to see a historical whitepaper floating in front of you, the scholarly critique that draws your first 100 subscribers, the founding document you publish to kick off your startup society.

Now let’s equip you with the tools to write it.

Microhistory and Macrohistory

In the bottom-up view, history is written to the ledger. If everything that happened gets faithfully recorded, history is then just the analysis of the log files. To understand this view we’ll discuss the idea of history as a trajectory. Then we’ll introduce the concepts of microhistory and macrohistory, by analogy to microeconomics and macroeconomics. Finally, we’ll unify all this with the new concept of cryptohistory.

History as a Cryptic Epic of Twisting Trajectories

What happens when you propel an object into the air? The first thing that comes to mind is the trajectory of a ball. Throw it and witness its arc. Just a simple parabola, an exercise in freshman physics. But there are more complicated trajectories.

- A boomerang flies forward and comes back to the origin.

- A charged particle in a constant magnetic field is subject to a force at right angles, and moves in a circle.

- A rocket with sufficient fuel can escape the earth’s atmosphere rather than coming back down.

- A curveball, subject to the Magnus effect, can twist in mid-air en route to its destination.

- A projectile launched into a sufficiently thick gelatin decelerates without ever hitting the ground.

- A powered drone can execute an arbitrarily complicated flight path, mimicking that of a bumblebee or helix.

So, how a system evolves with time — its trajectory — can be complex and counterintuitive, even for something small. This is a good analogy for history. If the flight path of a single inanimate object can be this surprising, think about the dynamics of a massive multi-agent system of highly animate people. Imagine billions of humans springing up on the map, forming clusters, careening into each other, creating more humans, and throwing off petabytes of data exhaust the whole way. That’s history.

And the timeframes involved make it tough to study. The rock you throw into the air doesn’t take decades to play out its flight path. Humans do. So a historical observer can literally die before seeing the consequences of an action.

Moreover, the subjects of the study don’t want to be studied. A mere rock isn’t a stealth bomber. It has neither the motive nor the means to deceive you about its flight path. Humans do. The people under the microscope are fogging the lens.

So: the scale is huge, the timeframe is long, and the measurements aren’t just noisy but intentionally corrupted.

We can encode all of this into a phrase: history is a cryptic epic of twisting trajectories. Cryptic, because the narrators are unreliable and often intentionally misleading. Epic, because the timescales are so long that you have to consciously sample beyond your own experience and beyond any human lifetime to see patterns. Twisting, because there are curves, cycles, collapses, and non-straightforward patterns. And trajectories, because history is ultimately about the time evolution of human beings, which maps to the physical idea of a dynamical system, of a set of particles progressing through time.

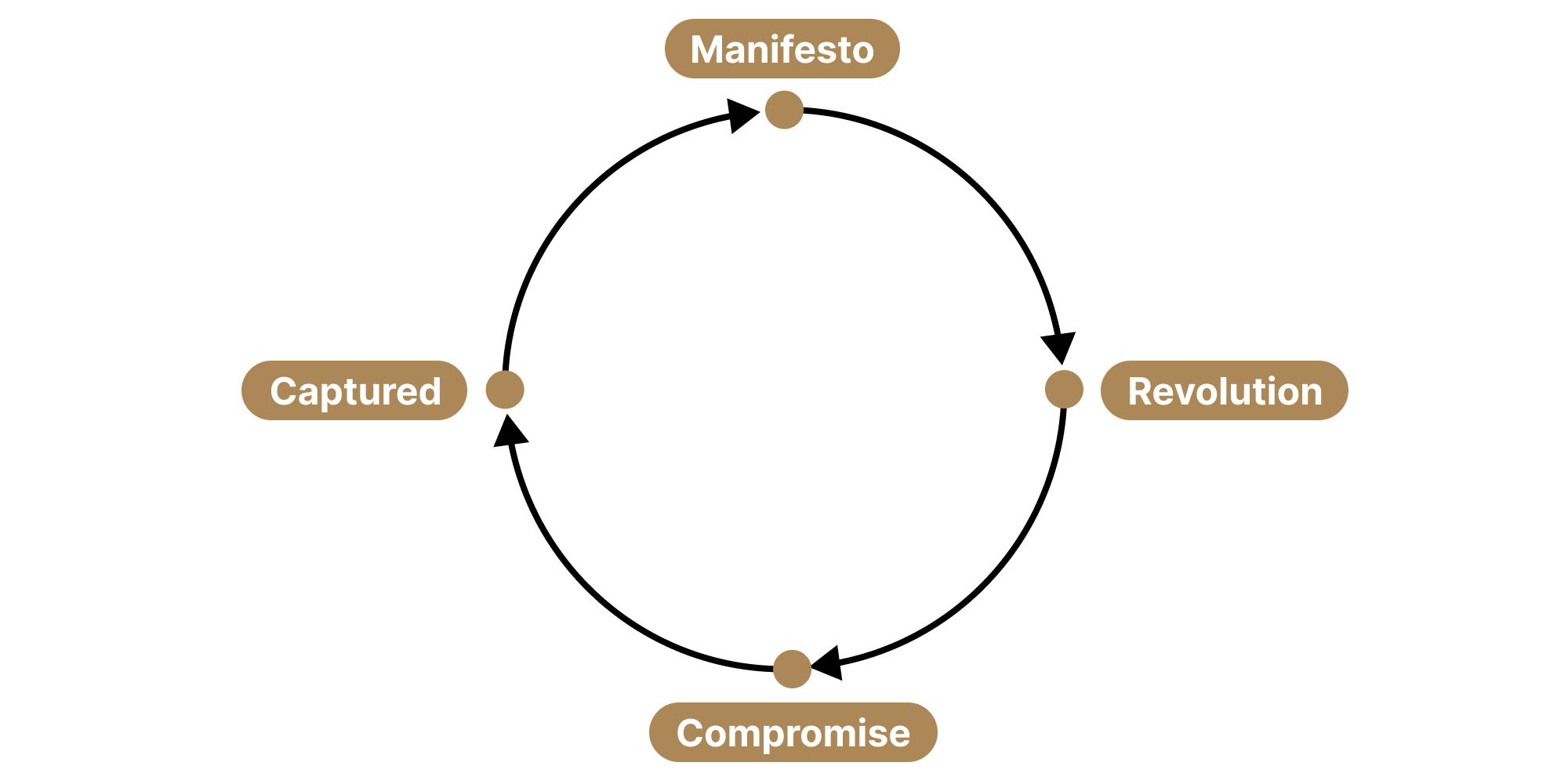

Put that together, and it wipes out both the base-rater’s view that today’s order will remain basically stable over the short-term, and the complementary view of a long-term “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” It also contests the idea that the fall of the bourgeoisie “and the victory of the proletariat are equally inevitable,” or that “no two countries on a Bitcoin standard will go to war with each other,” or even that technological progress has been rapid, so we can assume it will continue and society will not collapse.

Those phrases come from different ideologies, but each of them verbally expresses the clean parabolic arc of the rock. History isn’t really like that at all. It’s much more complicated. There are certainly trends, and those phrases do identify real trends, but there is also pushback to those trends, counterforces that arise in response to applied forces, syntheses that form from theses and antitheses, and outright collapses. Complex dynamics, in other words.

And how do we study complex dynamical systems? The first task is to measure.

Microhistory is the History of Reproducible Systems

Microhistory is the history of a reproducible system, one which has few enough variables that it can be reset and replayed from the beginning in a series of controlled experiments. It is history as a quantitative trajectory, history as a precise log of measurements. For example, it could be the record of all past values of a state space vector in a dynamical system, the account of all moves made by two deterministic algorithms playing chess against each other, or the chronicle of all instructions executed by a journaling file system after being restored to factory settings.

Microhistory is an applied subject, where accurate historical measurement is of direct technical and commercial importance. We can see this with technologies like the Kalman filter, which was used for steering the spaceship used in the moon landing. You can see the full technical details here, but roughly speaking the Kalman filter uses past measurements x[t−1],x[t−2],x[t−3] to inform the estimate of a system’s current state x[t], the action that should be taken u[t], and the corresponding prediction of the future state x[t+1] should that action be taken. For example, it uses past velocity, direction headings, fuel levels, and the like to recommend how a space shuttle should be steered at the current timestep. Crucially, if the microhistory is not accurate enough, if the confidence intervals around each measurement are too wide, or if (say) the velocity estimate is wrong altogether, then the Kalman Filter does not work and Apollo doesn’t happen.

At a surface level, the Kalman filter resembles the kind of time series analysis that’s common in finance. The key difference is that the Kalman filter is used on reproducible systems while finance is typically a non-reproducible system. If you’re using the Kalman filter to guide a drone from point A to point B, but you have a bug in your code and the drone crashes, you can simply pick up the drone85, put it back on the launch pad at point A, and try again. Because you can repeat the experiment over and over, you can eventually get very precise measurements and a functioning guidance algorithm. That’s a reproducible system.

In finance, however, you usually can’t just keep re-running a trading algorithm that makes money and get the same result. Eventually your counterparties will adapt and get wise. A key difference relative to our drone example is the presence of animate objects (other humans) who won’t always do the same thing given the same input.86 In fact, they can often be adversarial, observing and reacting to your actions, intentionally confounding your predictions, especially if they can profit from doing so. Past performance is no guarantee of future results in finance, as opposed to physics. Unlike the situation with the drone, a market isn’t a reproducible system.

Microhistory thus has its limits, but it’s an incredibly powerful concept. If we have good enough measurements on the past, then we have a better prediction of the future in an extremely literal sense. If we have tight confidence intervals on our measurements of the past, if the probability distribution P(x[t−1]) is highly peaked, then we get correspondingly tight confidence intervals on the present P(x[t]) and the future P(x[t+1]). Conversely, the more uncertainty about your past, the more confused you are about where you’re from and where you’re going, the more likely your rocket will crash. It’s Orwell more literally than he ever expected: he who controls the past controls the future, in the direct sense that he has better control theory. Only a civilization with a strong capacity for accurate microhistory could ever make it to the moon.

This is a powerful analogy for civilization. A group of people who doesn’t know who they are or where they came from won’t ever make it to the moon, let alone to Mars.

Can we make it more than an analogy?

Macrohistory is the History of Non-Reproducible Systems

Macrohistory is the history of a non-reproducible system, one which has too many variables to easily be reset and replayed from the beginning. It is history that is not directly amenable to controlled experiment. At small scale, that’s the unpredictable flow of a turbulent fluid; at very large scale, it’s the history of humanity.

We think of macrohistory as being on a continuum with microhistory. Why? We’ll make a few points and then tie them all together.

-

First, science progresses by taking phenomena formerly thought of as non-reproducible (and hence unpredictable) systems, isolating the key variables, and turning them into reproducible (and hence predictable) systems. For example, Koch’s postulates include the idea of transmission pathogenesis, which turned the vague concept of infection via “miasma” into a reproducible phenomenon: expose a mouse to a specific microorganism in a laboratory setting and an infection arises, but not otherwise.

-

Second, and relatedly, science progresses by improved instrumentation, by better recordkeeping. Star charts enabled celestial navigation. Johann Balmer’s documentation of the exact spacing of hydrogen’s emission spectra led to quantum mechanics. Gregor Mendel’s careful counting of pea plants led to modern genetics. Things we counted as simply beyond human ken — the stars, the atom, the genome — became things humans can comprehend by simply counting.

-

Third, how do we even know anything about the history of ancient Rome or Egypt or Medieval Europe? From artifacts and written records. Thousands of years ago, people were scratching customer reviews into a stone tablet, one of the first tablet-based apps. We know who Abelard and Heloise were from their letters to each other. We know what the Romans were like from what they recorded. To a significant extent, what we know about history is what we’ve recovered from what people wrote down.

-

Fourth, today, we have digital documentation on an unprecedented scale. We have billions of people using social media each day for almost a decade now. We also have billions of phones taking daily photographs and videos. We have countless data feeds of instruments. And we have massive hard drives to store it all. So, if reckoned on the basis of raw bytes, we likely record more information in a day than all of humanity recorded up to the year 1900. It is by far the most comprehensive log of human activity we’ve ever had.

We can now see the continuum87 between macrohistory and microhistory. We are collecting the kinds of precise, quantitative, microhistorical measurements that typically led to the emergence of a new science…but at the scale of billions of people, and going into our second decade.

So, another term for “Big Data” should be “Big History.” All data is a record of past events, sometimes the immediate past, sometimes the past of months or years ago, sometimes (in the case of Google Books or the Digital Michelangelo project) the past of decades or centuries ago. After all, what’s another word for data storage in a computer? Memory. Memory, as in the sense of human memory, and as in the sense of history.

That memory is commercially valuable. A technologist who neglects history ensures their users will get exploited. Proof? Consider reputation systems. Any scaled marketplace has them. The history of an Uber driver or rider’s on-platform behavior partially predicts their future behavior. Without years of star ratings, without memories of past actions of millions of people, these platforms would be wrecked by fraud. Macrohistory makes money.

This is just one example. There are huge short and long-term incentives to record all this data, all this microhistory and macrohistory. And future historians88 will study our digital log to understand what we were like as a civilization.

Bitcoin’s Blockchain Is a Technology for Robust Macrohistory

There are some catches to the concept of digital macrohistory, though: silos, bots, censors, and fakes. As we’ll show, Bitcoin and its generalizations provide a powerful way to solve these issues.

First, let’s understand the problems of silos, bots, censors, and fakes. The macrohistorical log is largely siloed across different corporate servers, on the premises of Twitter and Facebook and Google. The posts are typically not digitally signed or cryptographically timestamped, so much of the content is (or could be) from bots rather than humans. Inconvenient digital history can be deleted by putting sufficient pressure on centralized social media companies or academic publishers, censoring true information in the name of taking down “disinformation,” as we’ve already seen. And the advent of AI allows highly realistic fakes of the past and present to be generated. If we’re not careful, we could drown in fake data.

So, how could someone in the future (or even the present) know if a particular event they didn’t directly observe was real? The Bitcoin blockchain gives one answer. It is the most rigorous form of history yet known to man, a history that is technically and economically resistant to revision. Thanks to a combination of cryptographic primitives and financial incentives, it is very challenging to falsify the who, what, and when of transactions written to the Bitcoin blockchain.

Who initiated this transfer, what amount of Bitcoin did they send, what metadata did they attach to the transaction, and when did they send it? That information is recorded in the blockchain and sufficient to give a bare bones history of the entire Bitcoin economy since 2009. And if you sum up that entire history to the present day, you also get the values of how much BTC is held by each address. It’s an immediatist model of history, where the past is not even past - it’s with us at every second.

In a little more detail, why is the Bitcoin blockchain so resistant to the rewriting of history? To falsify the “who” of a single transaction you’d need to fake a digital signature, to falsify the “what” you’d need to break a hash function, to falsify the “when” you’d need to corrupt a timestamp, and you’d need to do this while somehow not breaking all the other records cryptographically connected to that transaction through the mechanism of composed block headers.

Some call the Bitcoin blockchain a timechain, because unlike many other blockchains, its proof-of-work mechanism and difficulty adjustment ensure a statistically regular time interval between blocks, crucial to its function as a digital history.

(I recognize that these concepts and some of what follows is technical. Our whirlwind tour may provoke either familiar head-nodding or confused head-scratching. If you want more detail, we’ve linked definitions of each term, but fully explaining them is beyond the scope of this work. However, see The Truth Machine for a popular treatment and Dan Boneh’s Cryptography course for technical detail.)

Nevertheless, here’s the point for even a nontechnical reader: the Bitcoin blockchain gives a history that’s hard to falsify. Unless there’s an advance in quantum computing, a breakthrough in pure math, a heretofore unseen bug in the code, or a highly expensive 51% attack that probably only China could muster, it is essentially infeasible to rewrite the history of the Bitcoin blockchain — or anything written to it. And even if such an event does happen, it wouldn’t be an instantaneous burning of Bitcoin’s Library of Alexandria. The hash function could be replaced with a quantum-safe version, or another chain robust to said attack could take Bitcoin’s place, and back up the ledger of all historical Bitcoin transactions to a new protocol.

With that said, we are not arguing that Bitcoin is infallible. We are arguing that it is the best technology yet invented for recording human history. And if the concept of cryptocurrency can endure past the invention of quantum decryption, we will likely think of the beginning of cryptographically verifiable history as on par with the beginning of written history millennia ago. Future societies may think of the year 2022 AD as the year 13 AS, with “After Satoshi” as the new “Anno Domini,” and the block clock as the new universal time.

The Bitcoin Blockchain Can Record Non-Bitcoin Events

For the price of a single transaction, the Bitcoin blockchain can be generalized to provide a cryptographically verifiable record of any historical event, a proof-of-existence.

For example, perhaps there is some off-chain event of significant importance where you want to store it for the record. Suppose it’s the famous photo of Stalin with his cronies, because you anticipate the rewriting of history. The proof-of-existence technique we’re about to describe wouldn’t directly be able to prove the data of the file was real, but you could establish the metadata on the file — the who, what, and when — to a future observer.

Specifically, given a proof-of-existence, a future observer would be able to confirm that a given digital signature (who) put a given hash of a photo (what) on chain at a given time (when). That future observer might well suspect the photo could still be fake, but they’d know it’d have to be faked at that precise time by the party controlling that wallet. And the evidence would be on-chain years before the airbrushed official photo of Stalin was released. That’s implausible under many models. Who’d fake something so specific years in advance? It’d be more likely the official photo was fake than the proof-of-existence.

So, let’s suppose that this limited level of proof was worth it to you. You are willing to pay such that future generations can see an indelible record of a bit of history. How would you get that proof onto the Bitcoin blockchain?

The way you’d do this is by organizing your arbitrarily large external

dataset (a photo, or something much larger than that) into a Merkle

tree, calculating a string of fixed length called a Merkle root, and

then writing that to the Bitcoin blockchain through OP_RETURN. This

furnishes a tool for proof-of-existence for any digital file.

You can do this as a one-off for a single piece of data, or as a periodic backup for any non-Bitcoin chain. So you could, in theory, put a digital summary of many gigabytes of data from another chain on the Bitcoin blockchain every ten minutes for the price of a single BTC transaction, thereby proving it existed. This would effectively “back up” this other blockchain and give it some of the irreversibility properties of Bitcoin. Call this kind of chain a subchain.

By analogy to the industrial use of gold, this type of “industrial” use case of a Bitcoin transaction may turn out to be quite important. A subchain with many millions of off-Bitcoin transactions every ten minutes could likely generate enough economic activity to easily pay for a single Bitcoin transaction.89

And as more people try to use the Bitcoin blockchain, given its capacity limits, it might turn out that only industrial use cases like this could afford to pay sufficient fees in this manner, as direct individual use of the Bitcoin blockchain could become expensive.

So, that means we can use the proof-of-existence technique to log arbitrary data to the Bitcoin blockchain, including data from other chains.

Blockchains Can Record the History of an Economy and Society

We just zoomed in to detail how you’d log a single transaction to the Bitcoin blockchain to prove any given historical event happened. Now let’s zoom out.

As noted, the full scope of what the Bitcoin blockchain represents is nothing less than the history of an entire economy. Every transaction is recorded since t=0. Every fraction of a BTC is accounted for, down to one hundred millionth of a Bitcoin. Nothing is lost.

Except, of course, for all the off-chain data that accompanies a transaction - like the identity of the sender and receiver, the reason for their transaction, the SKU of any goods sold, and so on. There are usually good reasons for these things to remain private, or partially private, so you might think this is a feature.

The problem is that Bitcoin’s design is a bit of a tweener, as it doesn’t actually ensure that public transactions remain private. Indeed there are companies like Elliptic and Chainalysis devoted entirely to the deanonymization of public Bitcoin addresses and transactions. The right model of the history of the Bitcoin economy is that it’s in a hybrid state, where the public has access to the raw transaction data, but private actors (like Chainalysis and Elliptic) have access to much more information and can deanonymize many transactions.

Moreover, Bitcoin can only execute Bitcoin transactions, rather than all the other kinds of digital operations you could facilitate with more blockspace. But people are working on all of this.

- Zero-knowledge technology like ZCash, Ironfish, and Tornado Cash allow on-chain attestation of exactly what people want to make public and nothing more.

- Smart contract chains like Ethereum and Solana extend the capability of what can be done on chain, at the expense of higher complexity.

- Decentralized social networks like Mirror and DeSo put social events on chain alongside financial transactions.

- Naming systems like the Ethereum Name Service (ENS) and Solana Name Service (SNS) attach identity to on-chain transactions.

- Incorporation systems allow the on-chain representation of corporate abstractions above the level of a mere transaction, like financial statements or even full programmable company-equivalents like DAOs.

- New proof techniques like proof-of-solvency and proof-of-location extend the set of things one can cryptographically prove on chain from the basic who/what/when of Bitcoin.

- Cryptocredentials, Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), Non-Transferable Fungibles (NTFs), and Soulbounds allow the representation of non-financial data on chain, like diplomas or endorsements.

What’s the point? If blockspace continues to increase, ever more of the digital history of our economy and society will be recorded on chain, in a cryptographically verifiable yet privacy-preserving way. The analogy is to the increase in bandwidth, which now allows us to download a megabyte of JavaScript on a mobile phone to run a webapp, an unthinkable indulgence in the year 2000.

This is a breakthrough in digital macrohistory that addresses the issues of silos, bots, censors, and fakes. Public blockchains aren’t siloed in corporations, but publicly accessible. They provide new tools, like staking and ENS-style identity, that allow separation of bots from humans. They can incorporate many different proof techniques, including proof-of-existence and more, to address the problem of deepfakes. And they can have very strong levels of censorship resistance by paying transaction fees to hash their chain state to the Bitcoin blockchain.

Cryptohistory is Cryptographically Verifiable Macrohistory

We can now see how the expansion of blockspace is on track to give us a cryptographically verifiable macrohistory, or cryptohistory for short.

This is the log of everything that billions of people choose to make public: every decentralized tweet, every public donation, every birth and death certificate, every marriage and citizenship record, every crypto domain registration, every merger and acquisition of an on-chain entity, every financial statement, every public record — all digitally signed, timestamped, and hashed in freely available public ledgers.90

The thing is, essentially all of human behavior has a digital component now. Every purchase and communication, every ride in an Uber, every swipe of a keycard, and every step with a Fitbit — all of that produces digital artifacts.

So, in theory you could eventually download the public blockchain of a network state to replay the entire cryptographically verified history of a community.89 That’s the future of public records, a concept that is to the paper-based system of the legacy state what paper records were to oral records.

It’s also a vision for what macrohistory will become. Not a scattered letter from an Abelard here and a stone tablet from an Egyptian there. But a full log, a cryptohistory. The unification of microhistory and macrohistory in one giant cryptographically verifiable dataset. We call this indelible, computable, digital, authenticatable history the ledger of record.

This concept is foundational to the network state. And it can be used for good or ill. In decentralized form, the ledger of record allows an individual to resist the Stalinist rewriting of the past. It is the ultimate expression of the bottom-up view of history as what’s written to the ledger. But you can also imagine a bastardized form, where the cryptographic checks are removed, the read/write access is centralized, and the idea of a total digital history is used by a state to create an NSA/China-like system of inescapable, lifelong surveillance.91

This in turn leads us to a top-down view of history, the future trajectory we want to avoid, where political power is used to defeat technological truth.

Political Power and Technological Truth

In the top-down view, history is written by the winners. It is about political power triumphing over technological truth.

Why does power care about the past? Because the morality of society is derived from its history. When the Chinese talk about Western imperialism, they aren’t just talking about some forgettable dust-up in the South China Sea, but how that relates to generations of colonialism and oppression, to the Eight Nations Alliance and the Opium Wars and so on. And when you see someone denounced on American Twitter as an x-ist, history is likewise being brought to bear. Again, why are they bad? Because of our history of x-ism…

As such, when you listen to a regime’s history, which you are doing every time you hear its official organs praise or denounce someone, you should listen critically.

Political Power as the Driving Force of History

How do the authorities use history? What techniques are they using? It’s not just a random collection of names and dates. They have proven techniques for sifting through the archives, for staffing a retinue of heros and villains from the past, for distilling the documents into (politically) useful parables. Here are two of them.

-

Political determinist model: history is written by the winners. People have heard this saying, but taking it seriously has profound implications. For example, whoever claims to be writing the “first draft of history” is therefore one of the winners. For another, history is what’s useful to the regime. A classic example is Katyn Forest: the admission that the Soviets did it would have delegitimized their postwar control over Poland during the 1945-1991 period, but once the USSR collapsed the truth could be revealed.

-

Political mascot model: history is written by winners pretending to be acting on behalf of losers. This is a variant of the political determinist model, also known as “offense archaeology,” and practiced by the modern American, Chinese, and Russian establishments — all of whom portray themselves as victims. The technique is to pick a mascot that the state claims to champion, such as the Soviet Union’s proletariat, and then go through history to find the worst examples of the state’s current rival doing something bad to them.

Take these real events, put them on the front page, and ensure everyone knows of them. Conversely, ensure off-narrative events are ignored or suppressed as taboo. Again taking the USSR as a case study, this involved finding endless (real!) examples of Western capitalists screwing the working class, and suppressing the worse (also real!) instances of Soviet communists gulaging their working class, as well as cases of the working class itself behaving badly. Generalization to other contexts is left as an exercise for the reader, but here’s a Russian example of what an American would call “responsibility to protect” (R2P).

These techniques are used to write history that favors a state. Here are more examples:

-

CCP China: Today’s Chinese media covers the Eight-Nations Alliance, the Opium Wars, and the like exhaustively in its domestic output, as these events show the malevolence of the European colonialists — who literally fought wars to keep China subjugated and addicted to heroin. Their domestic history does not mention the Uighurs, Tiananmen, and the like domestically. Xi’s CCP did stress the domestic problem of corruption via the “Tigers and Flies” campaign…but that’s in part because the anti-corruption campaign was politically useful against his internal enemies, and seemed not to ensnare his allies.

-

US Establishment: Today’s US establishment covers 6/4/1989 and the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War heavily, because they are real events that make China and Russia look bad and the US look good. It does not mention the 1900 Eight-Nations Alliance (when the US helped invade China with a “coalition of the willing” to defend European imperialism) or the 1932 Ukrainian Holodomor (when The New York Times Company’s Walter Duranty helped Soviet Russia choke out Ukraine) as these cut in the opposite direction.

The current US narrative also does not stress the Cultural Revolution (which bears too close a resemblance to present day America), or Western journalists like Edgar Snow who helped Mao come to power, or the full ugly history of American support for Russian and Chinese communism. This isn’t simply a matter of the age of events — after all, regime media goes back further in time when convenient, distorting events from 1619 for today’s headlines, yet somehow their time machine stutters on the years 1932 or 1900. In modern America, as in modern China, the history you hear about is the history the establishment finds to be politically useful against its internal and external rivals.

-

The British Empire: The British in both WW1 and WW2 understandably emphasized the evils of Germany, but not so much the evils of their ally Russia, or their own evils during the Opium Wars, or the desire for the Indian subcontinent to breathe free, and so on. (This one is almost too easy as the UK is no longer a contender for heavyweight champion of the world, so no one is offended when someone points out its past self-serving inconsistencies. Indeed, documenting the UK’s sins is now a cottage industry for Britain’s virtue signalers, as beating up on a beaten empire is far easier than tackling the taboos of a still live one.)

Point being: once you get your head out of the civilization you grew up in, and look at things comparatively, the techniques of political history become obvious. One of those techniques deserves special mention, and that’s a peacetime version of the “atrocity story”:

One of the most time-honored techniques to mobilize public animosity against the enemy and to justify military action is the atrocity story. This technique, says Professor Lasswell, has been used “with unvarying success in every conflict known to man.”

The concept is as useful in peacetime as it is in war. Why? Because states get their people hyped up to fight wars by stressing the essentially defensive nature of what they are doing and the savage behavior of the enemy. But war is politics by other means, so politics is war by other means. Even in peacetime, the state is predicated on force. And this use of force requires justification. The atrocity story is the tool used to convince people that the use of state force is legitimate.

Coming from a different vantage point, Rene Girard would call this a “founding murder.” Once you see this technique, you see it everywhere. Somewhat toned-down versions of the atrocity story are the go-to technique used to justify expansions of political power.

- If we don’t force people to take off their shoes at the airport, people will die!

- If we don’t stop people from voluntarily taking experimental curative drugs, people will die!

- If we don’t set up a disinformation office to stop people from making hostile comments online, people will die!

Indeed, almost everything in politics is backed by an atrocity story.92 There’s a sometimes real, sometimes fake, sometimes exaggerated Girardian founding murder (or at least founding injury) behind much of what the government does.

Sometimes the atrocity story is framed in terms of terrorists, sometimes in terms of children…but the general concept is “something so bad happened, we must use (state) force to prevent it from happening again.” Often this completely ignores the death caused by that force itself. For example, when the FDA “prevented” deaths by cracking down on drug approvals after thalidomide, it caused many more deaths via Eroom’s Law and drug lag.

And sometimes the atrocity story is just completely fake; before Iraq was falsely accused of holding WMD, it was falsely accused of tossing babies from incubators.

With that said, it’s possible to overcorrect here. Just because there is an incentive to fake (or exaggerate) atrocities does not mean that all atrocities are fake or exaggerated.93 Yes, you should be aware that states are always “flopping,” exaggerating the severity of the fouls against them or the mascots they claim to represent, trying to bring in the public on their side, whether they are Chinese or American or Russian.

But once you’re aware of the political power model of history, the next goal is to guard against both the Scylla and the Charybdis, against being too credulous and too cynical. Because just as the atrocity story is a tool for political power, unfortunately so too is genocide denial — as we can see from The New York Times’ Pulitzer-winning coverup of Stalin’s Ukrainian famine.

To maintain this balance, to know when states are lying or not, we need a form of truth powerful enough to stand outside any state and judge it from above. A way to respond to official statistics not with either reflexive faith or disbelief, but with dispassionate, independent calculation.

The bottom-up cryptohistory we introduced in the previous section is clearly relevant. But to fully appreciate it we need an allied theory: the technological truth theory of history.

Technological Truth as the Driving Force of History

The political power model of history gives us a useful lens: history is often just Leninist who/whom and Schmittian friend/enemy. But it’s a little parched94 to say that history is always and only that, solely about the raw exercise of political power. After all, a society must pass down true facts about nature, for example, or else its crops will not grow95 — and its political class will lose power.

This leads to a different set of tech-focused lenses for analyzing history.

-

Technological determinist model: technology is the driving force of history. While the political determinist model stresses that history is written — and hence distorted — by the winners, and thereby propagates only that which is useful to a given state, the technological determinist model notes that there are some key areas — principally in science and technology — where many (if not most) societies derive a benefit from passing down a technical fact without distortion. There is after all an unbroken chain from Archimedes, Aryabhata, Al-Kwarizhmi, and antiquity to all our existing science and technology. Hundreds of years later, we don’t care that much about the laws of Isaac Newton’s time, but we do care about Newton’s laws. In this model, all political ideologies have been around for all time — the only thing that changes is whether a given ideology is now technologically feasible as an organizing system for humanity. Thus: political fashions just come and go in cycles, so the absolute measure of societal progress is a culture’s level of technological advancement on something like the Kardashev scale.

-

Trajectory model: histories are trajectories. We mentioned this concept before when we discussed history as a cryptic epic of twisting trajectories, but it’s worth reprising. If you’re technically inclined, you might wonder why we spend so much time on history in this book. One answer is that histories are trajectories of dynamical systems. If you can spend your entire life studying wave equations, diffusion equations, time series, or the Navier-Stokes equations — and you can — you can do the same for the dynamics of people. In more detail, we know from physics (and Stephen Wolfram!) that very simple rules can produce incredibly complicated trajectories of dynamical systems. For Navier-Stokes, for example, we can divide these trajectories up into laminar flow, turbulent flow, inviscid flow, incompressible flow, and so on, to describe different ways a velocity field can evolve over time. These classifications are derived from measurements made of fluids over time. And the study of just one of these trajectory types can be a whole research discipline.

That’s how rich the dynamics of inanimate objects are. Now compare that to the macroscopic movements of millions of intelligent agents. You can similarly try to derive rules about how humans behave under situations of laminar good times, turbulent revolutionary times, and so on by studying the records we have of human behavior — the data exhaust that humans produce.

This analogy is actually very tight if you think about virtual economies and the history of human behavior on social networks and cryptosystems. In the fullness of time, with truly open datasets, we may even be able to develop Asimovian psychohistory from all the data recorded in the ledger of record, namely a way to predict the macroscopic behavior of humans in certain situations without knowing every microscopic detail. We can already somewhat do this for constructed environments like games96 and markets, and ever more human environments are becoming literally digitally constructed.97

-

Statistical model: history aids predictions. From a statistician’s perspective, history is necessary for accurately computing the future. See any time series analysis or machine learning paper — or the Kalman filter, which makes this concept very explicit. To paraphrase Orwell, without a quantitatively accurate record of the past you cannot control the future, in the sense that your control theory literally won’t work.

-

Helix model: linear and cyclical history can coexist. From a progressive’s perspective, history is a linear trend, where the “arc of history” bends towards freedom, and where those against a given cause are on the wrong side of history98. Others think of history as cyclical, a constant loop where the only thing these technologists are doing is reinventing the wheel, or where “strong men create good times, good times create weak men, weak men create hard times, and hard times create strong men.” But there’s a third view, a helical view of history, which says that from one viewpoint history is indeed progressive, from another it’s genuinely cyclical, and the reconciliation is that we move a bit forward technologically with each turn of the corkscrew rather than collapsing. In this view, attempts to restore the immediate preceding state are unlikely, as they’re rewinding the clock — but you might be able to get to a good state by winding the helix all the way past 12’o’clock to get the reboot. Or you might just collapse.

-

Ozymandias model: civilization can collapse. History shows us that technological progress is not inevitable. The Fall of Civilizations podcast really makes this clear. Gobekli Tepe is one example. Whether you’re thinking of this as an astronomer (where are all the intelligent life forms out there? Is the universe a dark forest?) or an anthropologist (how did all these advanced civilizations just completely die out?), it’s sobering to think that our civilization may just be like the best player in a video game so far: we’ve made it the furthest, but we have no guarantee that we’re going to win before killing ourselves99 and wiping out like all the other civilizations before us.

-

Lenski model: organisms are not ordinal. Richard Lenski ran a famous series of long-term evolution experiments with E. coli where he picked out a fresh culture of bacteria each day, froze it down in suspended animation, and thereby saved a snapshot of what each day of evolution looked like over the course of decades. The amazing thing about bacteria is that they can be unfrozen and reanimated, so Lenski could take an old E. coli strain from day 1173 and put it into a test tube with today’s strain to see who’d reproduce the most in a head-to-head competition. The result showed that history is not strictly ordinal; just because the day 1174 strain had outcompeted the day 1173 strain, and the day 1175 strain had outcompeted the day 1174 strain, and so on — does not necessarily mean that today’s strain will always win a head to head with the strain from day 1173. The complexity of biology is such that it’s more like an unpredictable game of rock/paper/scissors.

-

Train Crash model: those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it. Another way to think about history is as a set of expensive experiments, where people often made certain choices that seemed reasonable at the time and ended up in calamitous straits. That’s communism, for example: a persuasive idea for many, but one that history shows to not actually produce great results in practice.

-

Idea Maze model: those who overfit to history will never invent the future. This is the counterargument to the Train Crash model — past results may not predict future performance, and sometimes you need to have a beginner’s mindset to innovate. Generally this works better for opt-in technologies and investments than top-down modifications of society like communism. One tool for this comes from a concept I wrote up a while ago called the idea maze. The relevant bit here is that just because a business proposition didn’t work in the past doesn’t necessarily mean it won’t work today. The technological and social prerequisites may have dramatically changed, and doors previously closed may now have opened. Unlike the laws of physics, society is not time invariant. As even the world’s leading anti-tech blog once admitted:

Virtual reality was an abject failure right up to the moment it wasn’t. In this way, it has followed the course charted by a few other breakout technologies. They don’t evolve in an iterative way, gradually gaining usefulness. Instead, they seem hardly to advance at all, moving forward in fits and starts, through shame spirals and bankruptcies and hype and defensive crouches — until one day, in a sudden about-face, they utterly, totally win.

-

Wright-Fisher model: history is what survives natural selection. In population genetics, there’s an important model of how mutations arise and spread called the Wright-Fisher model. When a new mutation arises, it’s in only 1 out of N people. How does it get to N out of N, to 100%, to what’s called “fixation”? Well, first, it might not ever do that. It might just die out. It might also get to N out of N simply by luck, if the population of N is small — this is known as “fixation by genetic drift,” where those with the mutation just happen to reproduce more than others. But if the mutation confers some selective advantage s, if it aids in the reproduction of its host in a competitive environment, then it has a better than luck chance of getting to 100%. Similarly, those historical ideas that we’ve heard about can be thought of as those that aided or at least did not interfere with the propagation of their respective carriers, often the authorities that write those histories. Some of these ideas have tagged along by dumb luck, while others are claims that were selectively advantageous to the success of the regime - often by delegitimizing their rivals and legitimizing their own rule, or by giving them new technologies. This is a theory of memetic evolution; the ideological mutations that add technological edge or political power are the ones selected for.

-

Computational model: history is the on-chain population; all the rest is editorialization. There’s a great book by Franco Moretti called Graphs, Maps, and Trees. It’s a computational study of literature. Moretti’s argument is that every other study of literature is inherently biased. The selection of which books to discuss is itself an implicit editorialization. He instead makes this completely explicit by creating a dataset of full texts, and writing code to produce graphs. The argument here is that only a computational history can represent the full population in a statistical sense; anything else is just a biased sample.

-

Genomic model: history is what DNA (and languages, and artifacts) show us. David Reich’s Who We Are and How We Got Here is the canonical popular summary of this school of thought, along with Cavalli-Sforza’s older book on the History and Geography of Human Genes. The brief argument is: our true history is written in our genes. Mere texts can be faked, distorted, or lost, but genomics (modern or ancient) can’t be. Languages and artifacts are a bit less robust in terms of the signal for historical reconstruction, though they often map to what the new genomic studies are showing about patterns of ancient migrations.

-

Tech Tree model: history is great men constrained by the adjacent possible. As context, the great man theory of history says that individuals like Isaac Newton and Winston Churchill shaped events. The counterargument says that these men were carried on tides larger than them, and that others would have done the same in their place. For example, for many (not all) Newtons, there is a Leibniz, who could also have invented calculus. It’s impossible to fully test either of these theories without a Lenski-like experiment where we re-run history with the same initial conditions, but a useful model to reconcile the two perspectives is the tech tree from Civilization. Briefly, all known science represents the frontier of the tree, and an individual can choose to extend that tree in a given direction. There wasn’t really a Leibniz for Satoshi, for example; at a time when others were focused on social, mobile, and local, he was working on a completely different paradigm. But he was constrained by the available subroutines, concepts like Hashcash and chained timestamps and elliptic curves. Just like da Vinci could have conceived a helicopter, but probably not built it with the materials then available, the tech tree model allows for individual agency but subjects it to the constraint of what is achievable by one person in a given era. The major advantage of a tech tree is that (like the idea maze) it can be made visible, and navigable, as has been done for longevity by the Foresight Institute.

You might find it a bit surprising that there are as many different models for understanding history — let’s call them historical heuristics — as there are programming paradigms. Why might this be so? Well, just like the idea of statecraft strategies that we introduce later, the study of history can also be analogized to a type of programming, or at least data analysis. That is, history is the analysis of the log files.

-

Data exhaust model: history as the analysis of the log files. Here, we mean “log files” in the most general sense of everything society has written down or left behind; the documents, yes, but also the physical artifacts and genes and artwork, just like a log “file” can contain binary objects and not just plain text.

Extending the analogy, you can try to debug a program by flying blind without the logs, or alternatively you can try to look at every row of the logs, but rather than either of these extremes you’ll do best if you have a method for distilling the logs into something actionable.

And that’s why historical heuristics exist. They are strategies for distilling insight from all the documents, genes, languages, transactions, inventions, collapses, and successes of people over time. History is the entire record of everything humanity has done. It’s a very rich data structure that we have only begun to even think of as a data structure.

We can now think of written history as an (incomplete, biased, noisy) distillation of this full log. After all, if you’ve ever found a reporter’s summary of an eyewitness video to be wanting, or found a single video misleading relative to multiple camera angles, you’ll realize why having access to the full log of public events is a huge step forward.

A Collision of Political Power and Technological Truth

We’ve now defined a top-down and bottom-up model of history. The collision of these two models, of the establishment’s Orwellian relativism100 and the absolute truth of the Bitcoin blockchain, of political power and technological truth…that collision is worth studying.

Let’s do three concrete examples where political power has encountered technological truth.

- Tesla > NYT. Elon Musk used the instrumental record of a Tesla drive to knock down an NYT story. The New York Times Company claimed the car had run out of charge, but his dataset showed they had purposefully driven it around to make this happen, lying about their driving history. His numbers overturned their letters.

- Timestamp > Macron, NYT. Twitter posters used a photo’s timestamp to disprove a purported photo of the Brazilian fires that was tweeted by Emmanuel Macron and printed uncritically by NYT. The photo was shown via reverse image search to be taken by a photographer who had died in 2003, so it was more than a decade old. This was a big deal because The Atlantic was literally calling for war with Brazil over these (fake) photos.

- Provable patent priority. A Chinese court used an on-chain timestamp to establish priority in a patent suit. One company proved that it could not have infringed the patent of the other, because it had filed “on chain” before the other company had filed.

In the first and second examples, the employees of the New York Times Company simply misrepresented the facts as they are wont to do, circulating assertions that were politically useful against two of their perennial opponents: the tech founder and the foreign conservative. Whether these misrepresentations were made intentionally or out of “too good to check” carelessness, they were both attempts to exercise political power that ran into the brick wall of technological truth. In the third example, the Chinese political system delegated the job of finding out what was true to the blockchain.

In all three cases, technology provided a more robust means of determining what was true than the previous gold standards — whether that be the “paper of record” or the party-state. It decentralized the determination of truth away from the centralized establishment.

A Definition of Political and Technological Truths

It isn’t always possible to decentralize the determination of truth away from a political establishment. Some truths are intrinsically relative (and hence political), whereas others are amenable to absolute verification (and hence technological).

Here’s the key: is it true if others believe it to be true, or is it true regardless of what people believe?

A political truth is true if everyone believes it to be true. Things like money, status, and borders are in this category. You can change these by rewriting facts in people’s brains. For example, the question of what a dollar is worth, who the president is, and where the border of a country is are all dependent on the ideas installed in people’s heads. If enough people change their minds, markets move, presidents change, and borders shift.101

Conversely, a technical truth is true even if no human believes it to be true. Facts in math, physics, and biochemistry are in this category. They exist independent of what’s in people’s brains. For example, what’s the value of π, the speed of light, or the diameter of a virus? 102

Those are the two extremes: political truths that you can change by rewriting the software in people’s brains, and technical truths that exist independent of that.

A Balance of Political Power and Technological Truth

Once you reluctantly recognize that not every aspect of a sociopolitical order can be derived from an objective calculation, and that some things really do depend on an arbitrary consensus, you realize that we need to maintain a balance between political power and technological truth.103

Towards this end, the Chinese have a pithy saying: the backwards will be beaten. If you’re bad at technology, you’ll be beaten politically. Conversely, the Americans also have a saying: “you and what army?” It doesn’t matter how good you are as an individual technologist if you’re badly outnumbered politically. And if you’re unpopular enough, you won’t have the political power to build in the physical world.